8 of

You are browsing the full text of the article: The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games

Click here to go back to the list of articles for

Issue:

Volume: 1 of Design For Today

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 290 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 291 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 292 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 293 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

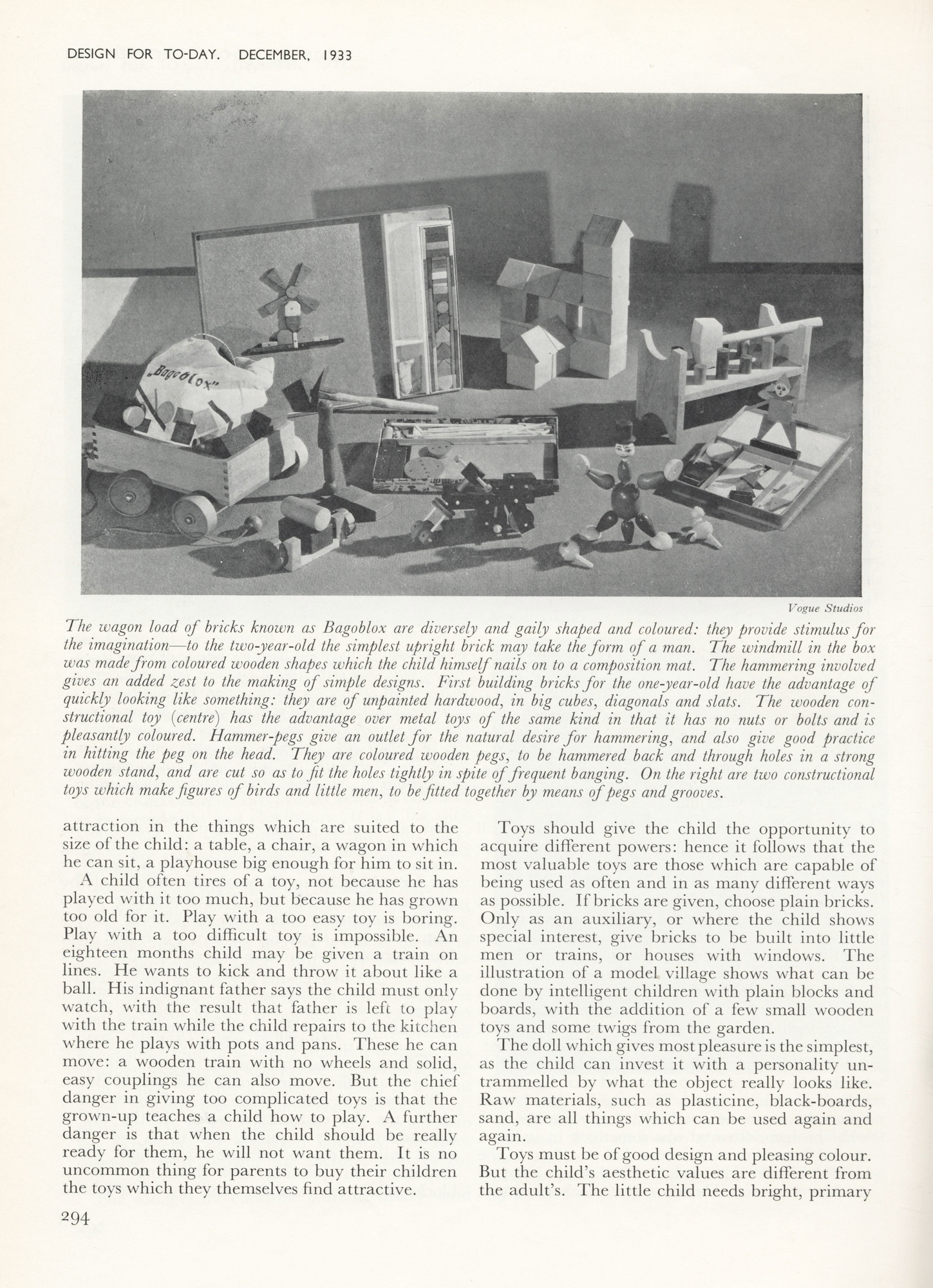

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 294 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 295 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

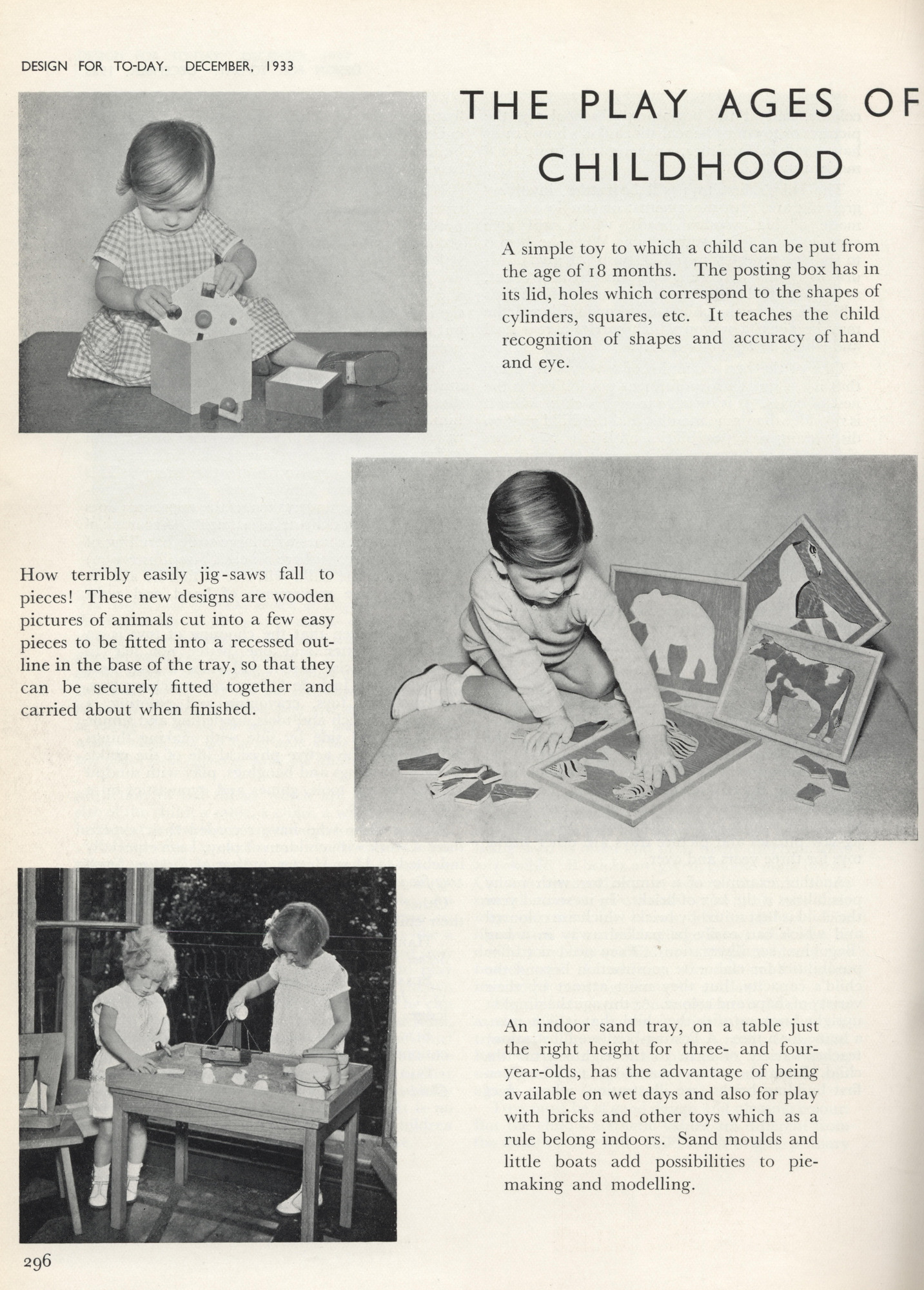

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 296 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

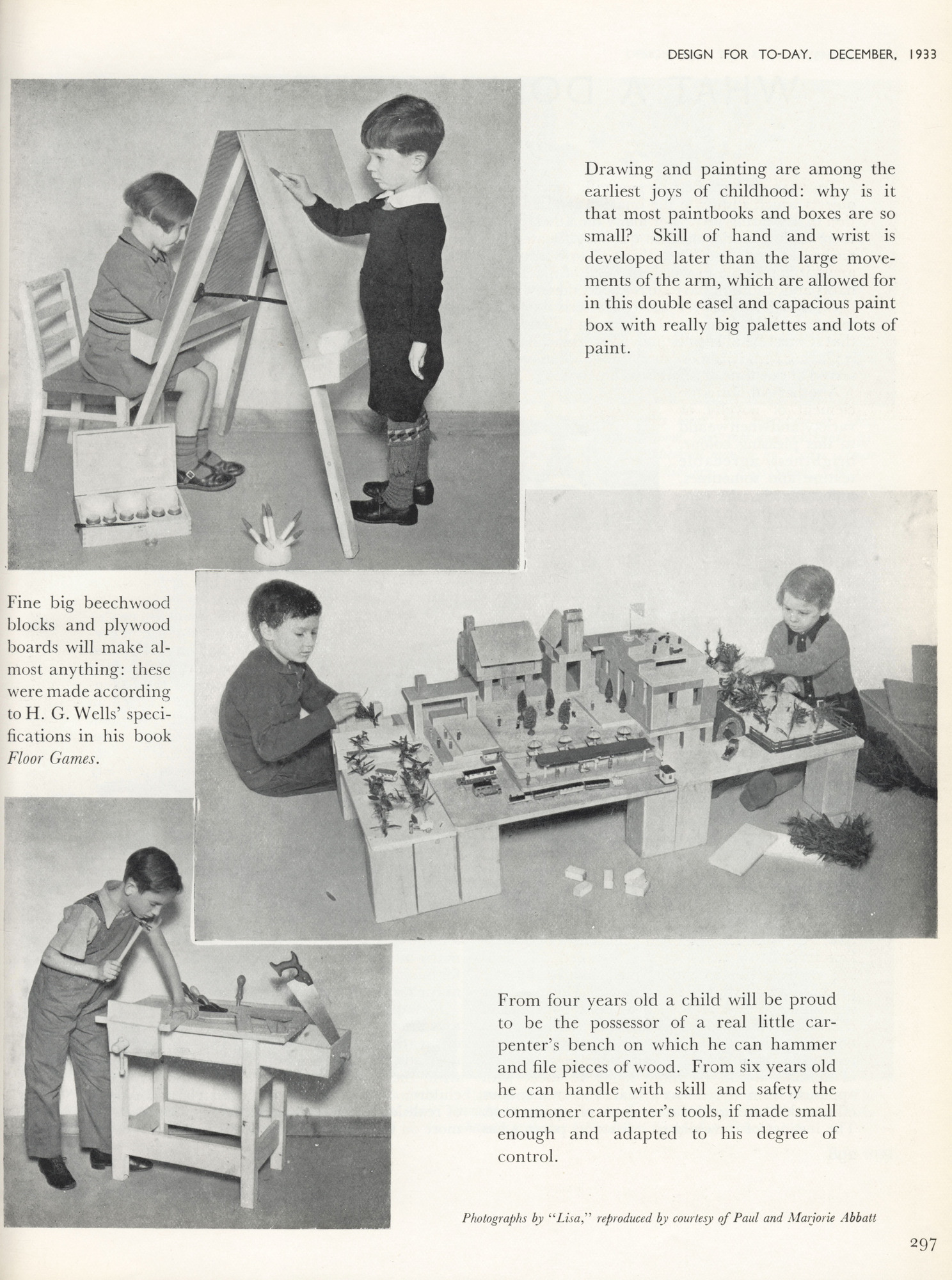

| Design For Today 1 1933 Page: 297 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Child's World: Psychology in Toys and Games | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||