6 of

You are browsing the full text of the article: The Prayer of A. O. Barnabooth

Click here to go back to the list of articles for

Issue:

Volume: 1 of The New Coterie

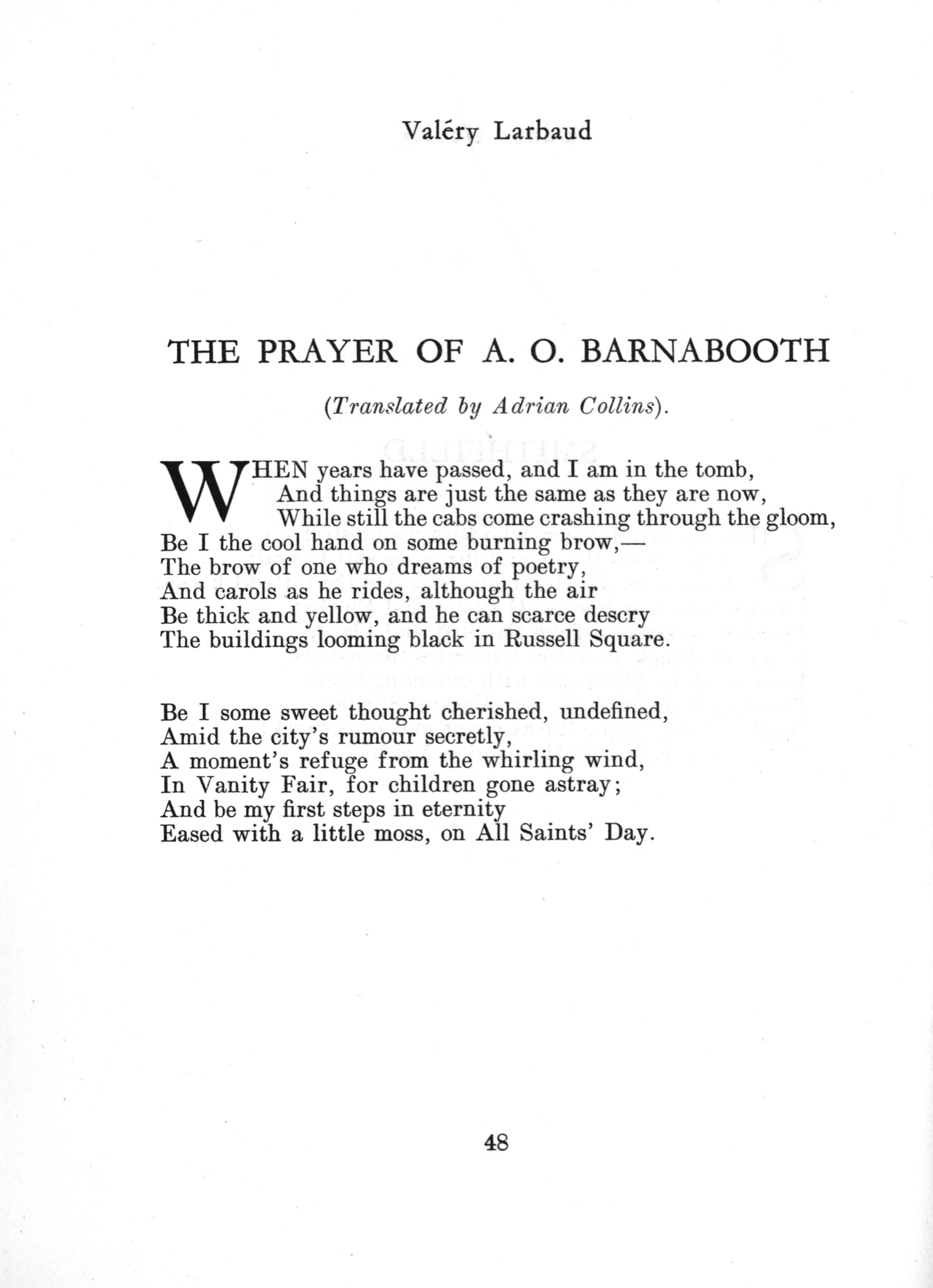

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 6 Summer & Autumn, 1927 Page: 48 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Prayer of A. O. Barnabooth By Valéry Larbaud | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

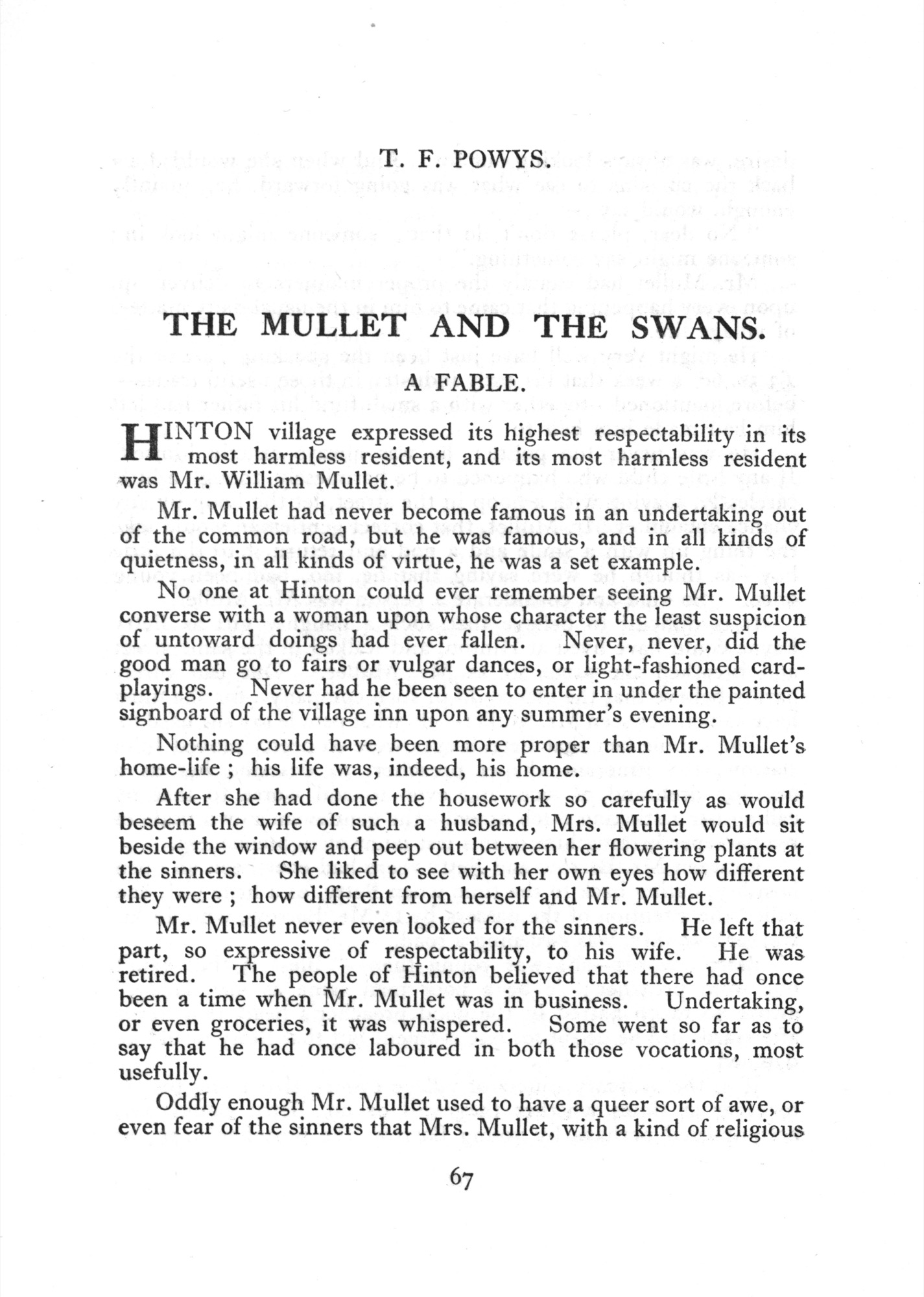

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 1 November, 1925 Page: 67 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Prayer of A. O. Barnabooth By Valéry Larbaud | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

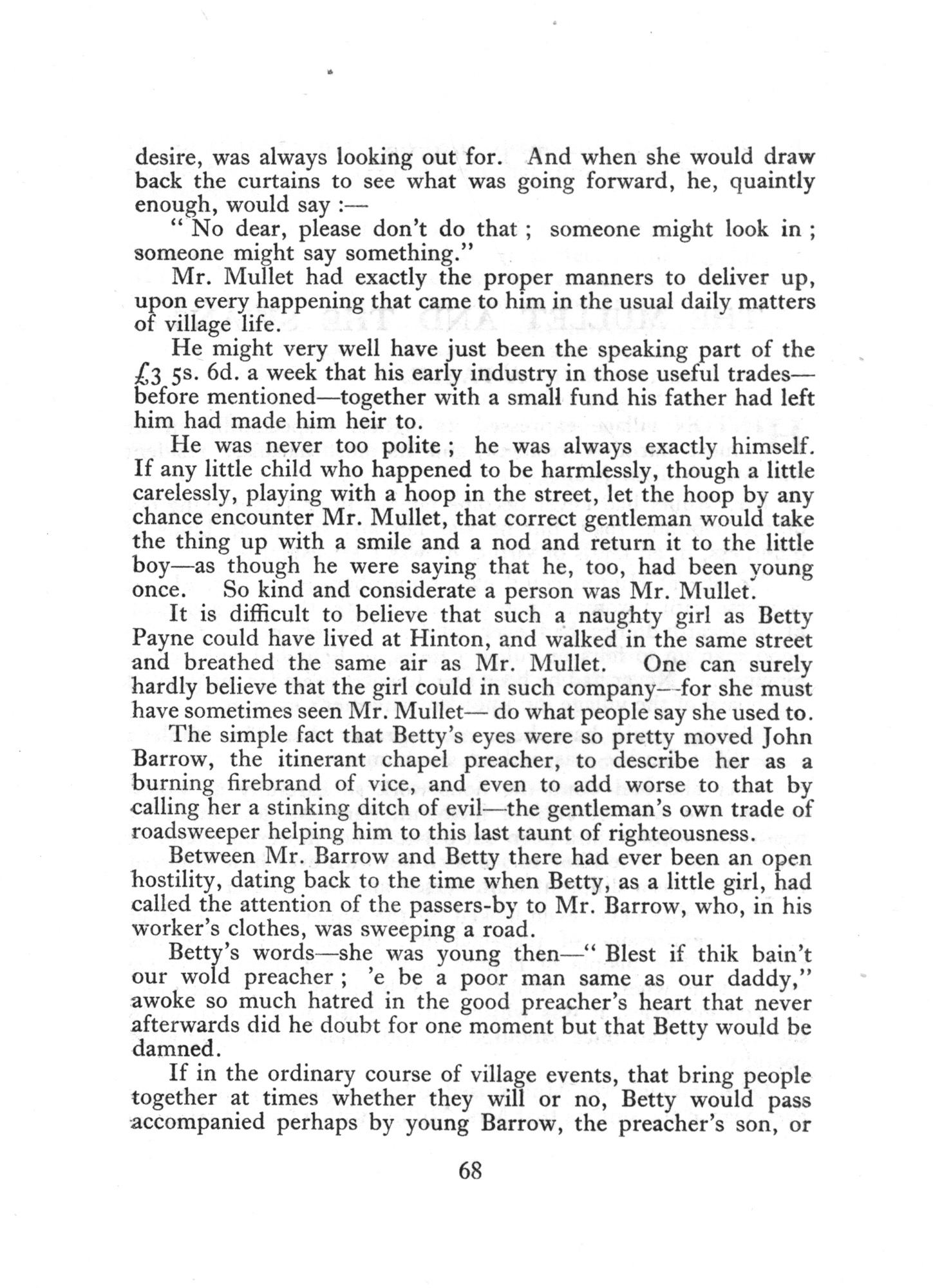

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 1 November, 1925 Page: 68 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Prayer of A. O. Barnabooth By Valéry Larbaud | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

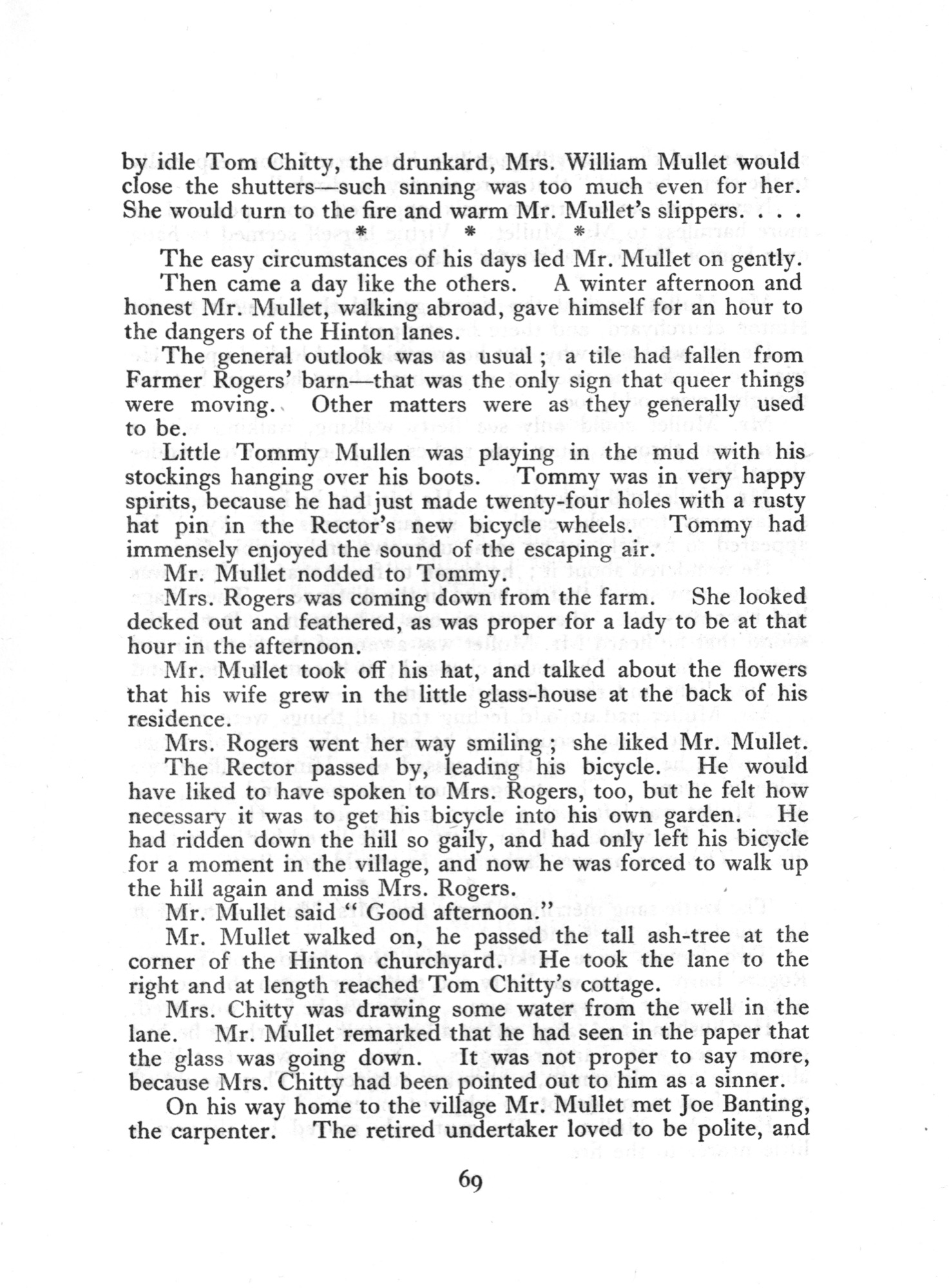

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 1 November, 1925 Page: 69 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Prayer of A. O. Barnabooth By Valéry Larbaud | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 1 November, 1925 Page: 70 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Prayer of A. O. Barnabooth By Valéry Larbaud | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||