4 of

You are browsing the full text of the article: The Grasshopper. A Short Story

Click here to go back to the list of articles for

Issue:

Volume: 1 of The New Coterie

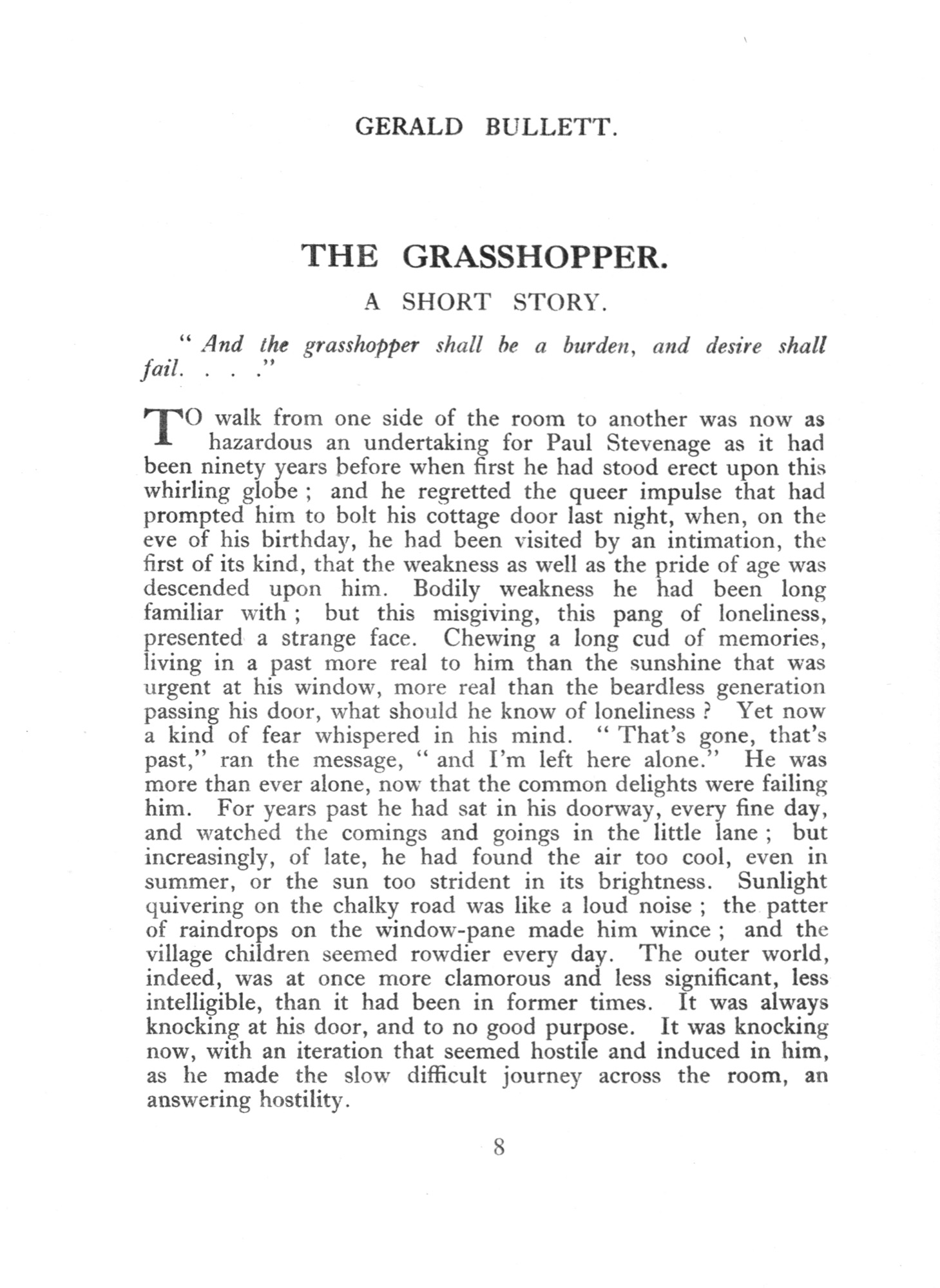

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

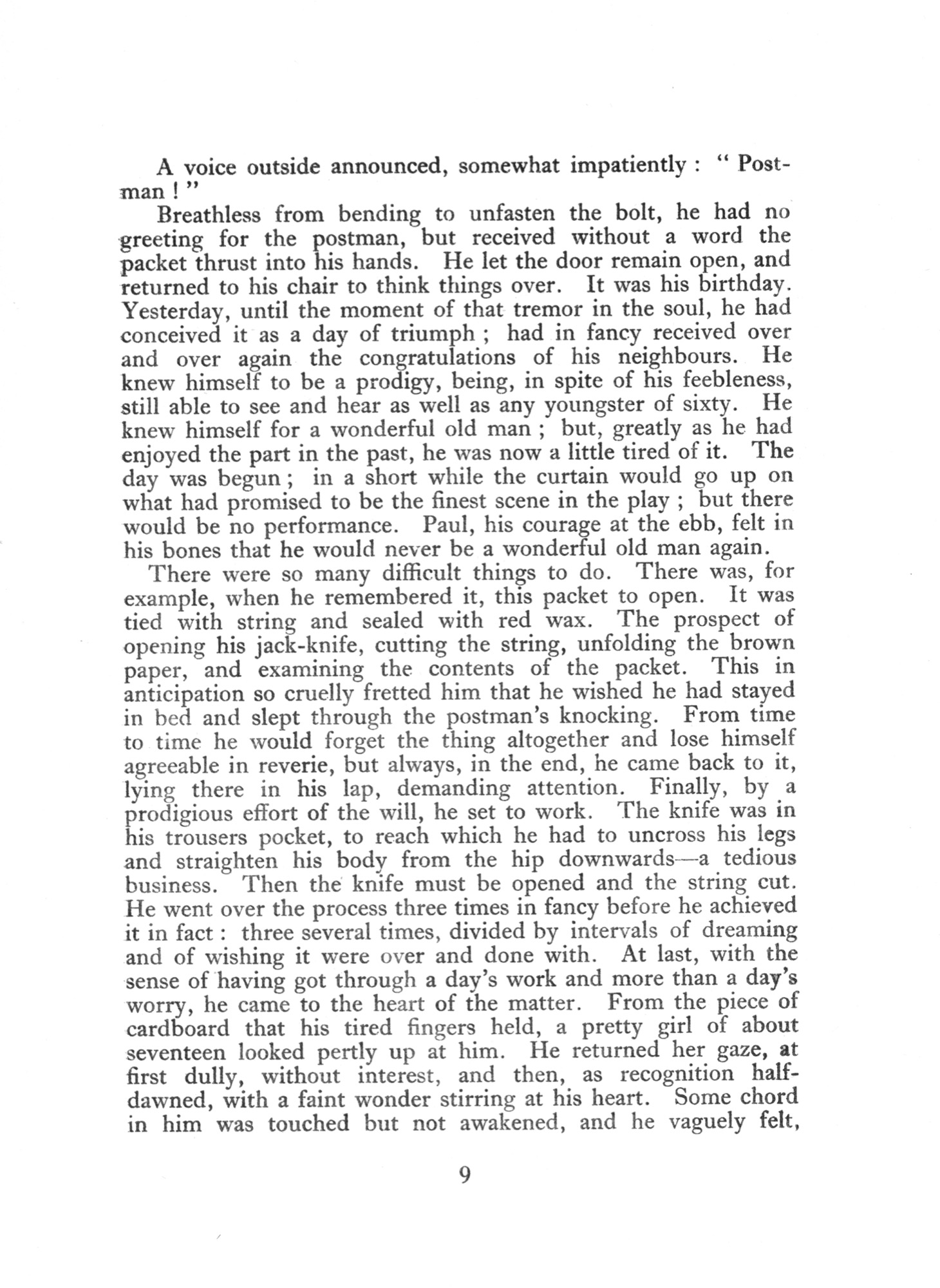

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

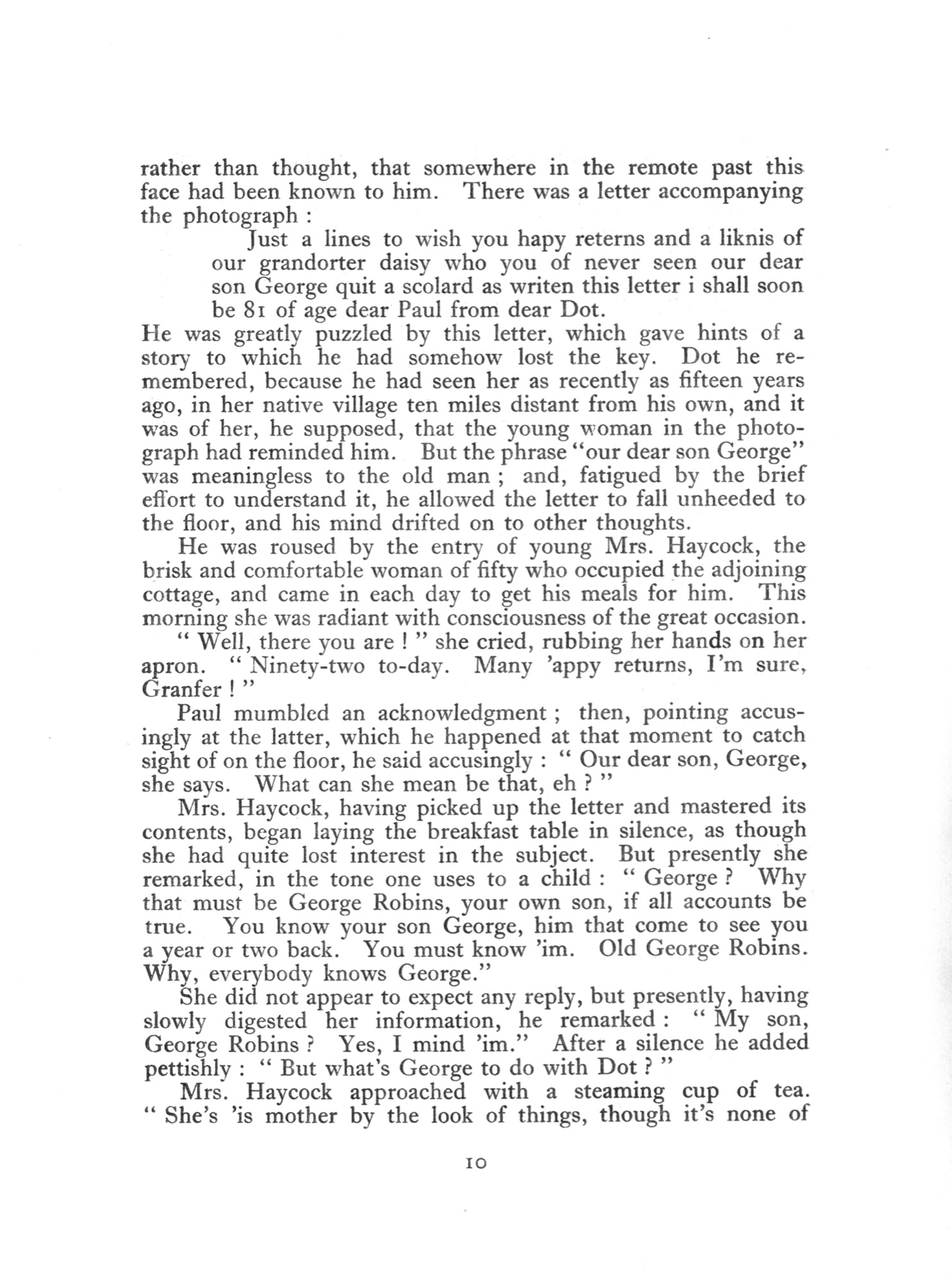

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

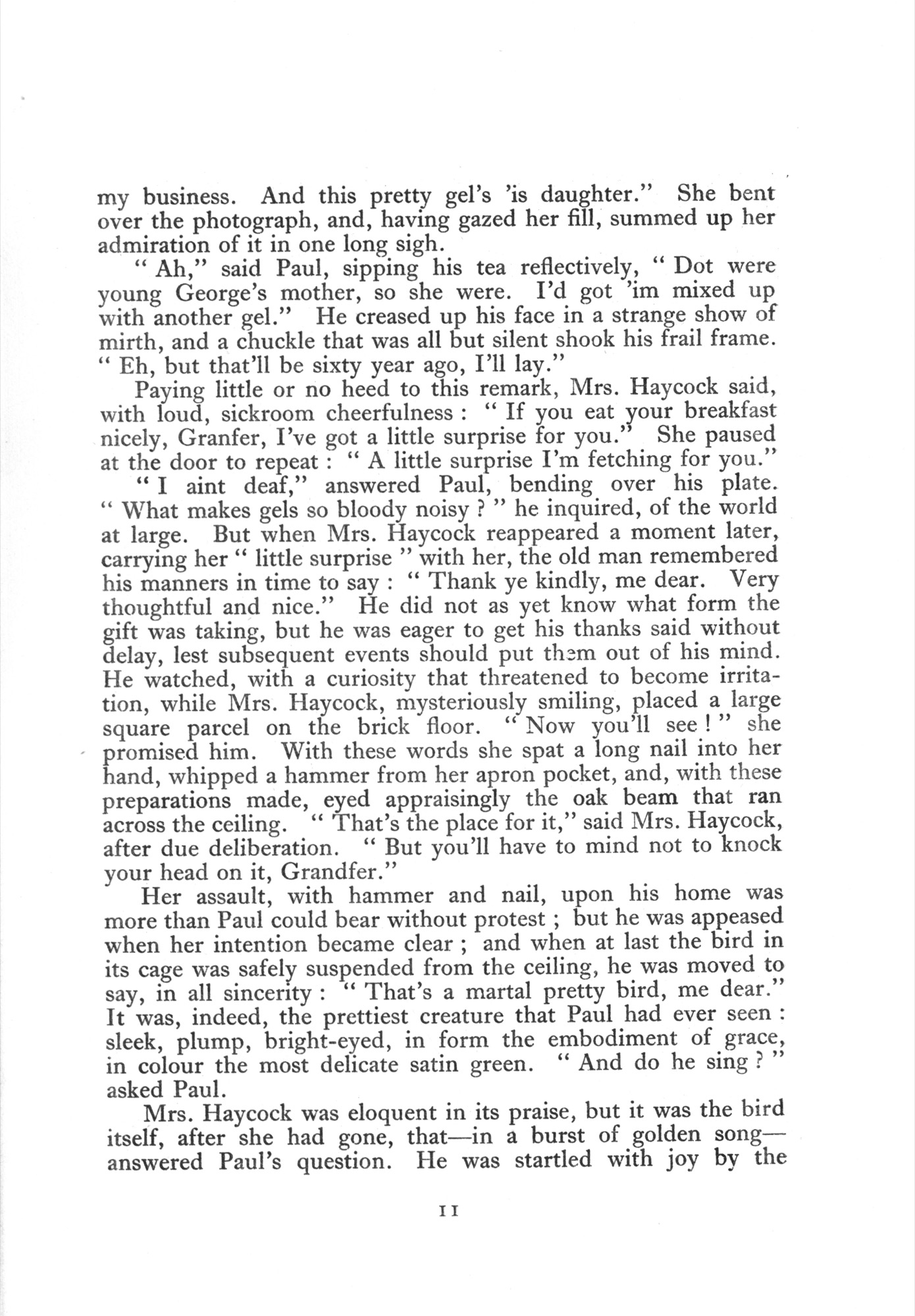

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The New Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 4 Autumn, 1926 Page: 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Grasshopper. A Short Story By Gerald Bullett | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||