1 of

You are browsing the full text of the article: Jules Dupré

Click here to go back to the list of articles for

Issue:

Volume: 1 of The Art Review

| The Art Review Volume 1 Issue: 1 January 1890 Page: 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jules Dupré By Julia M. Ady | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Art Review Volume 1 Issue: 1 January 1890 Page: 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jules Dupré By Julia M. Ady | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Art Review Volume 1 Issue: 1 January 1890 Page: - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

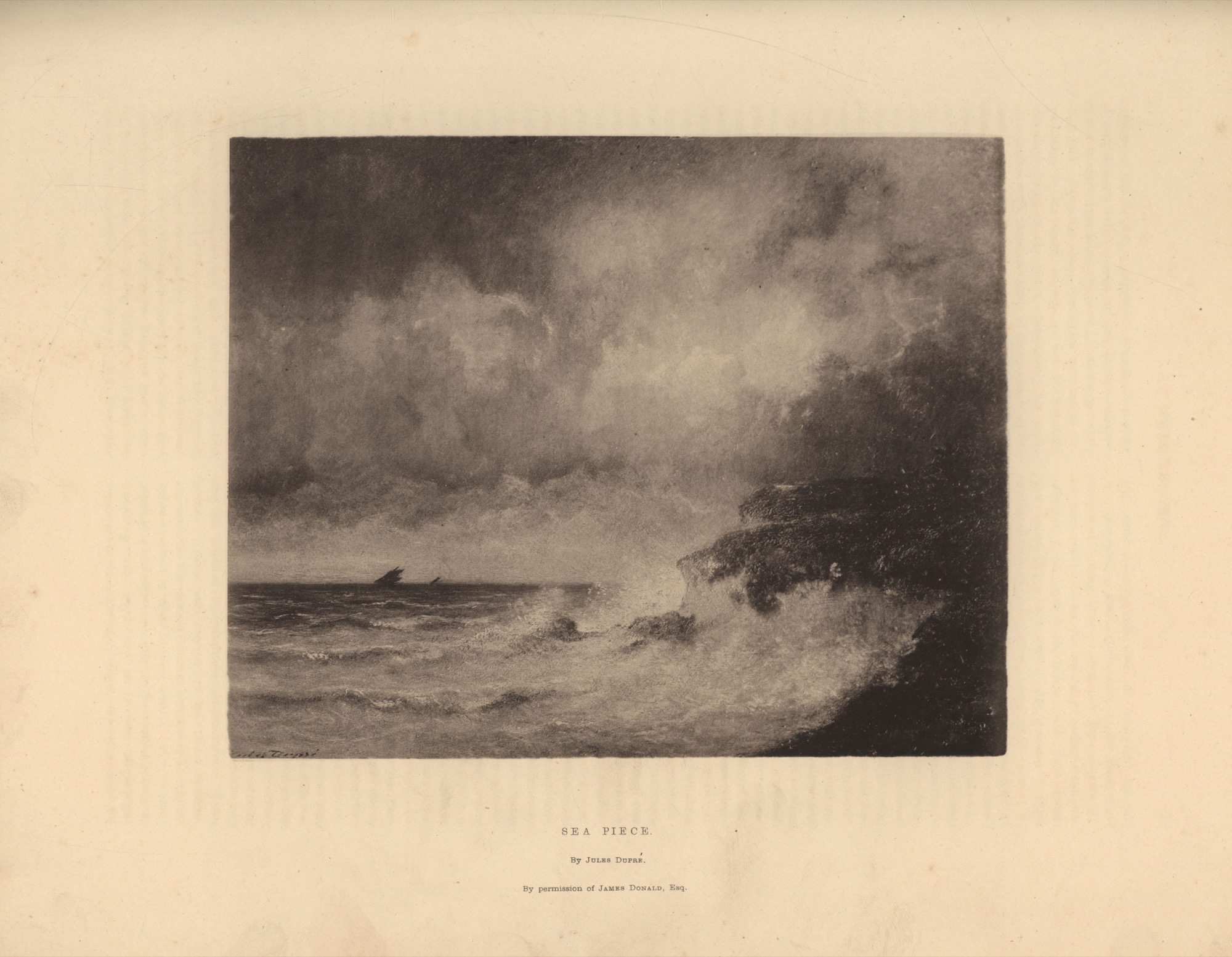

| Jules Dupré By Julia M. Ady | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Art Review Volume 1 Issue: 1 January 1890 Page: 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jules Dupré By Julia M. Ady | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||