5 of

You are browsing the full text of the article: The Return

Click here to go back to the list of articles for

Issue:

Volume: 1 of Coterie

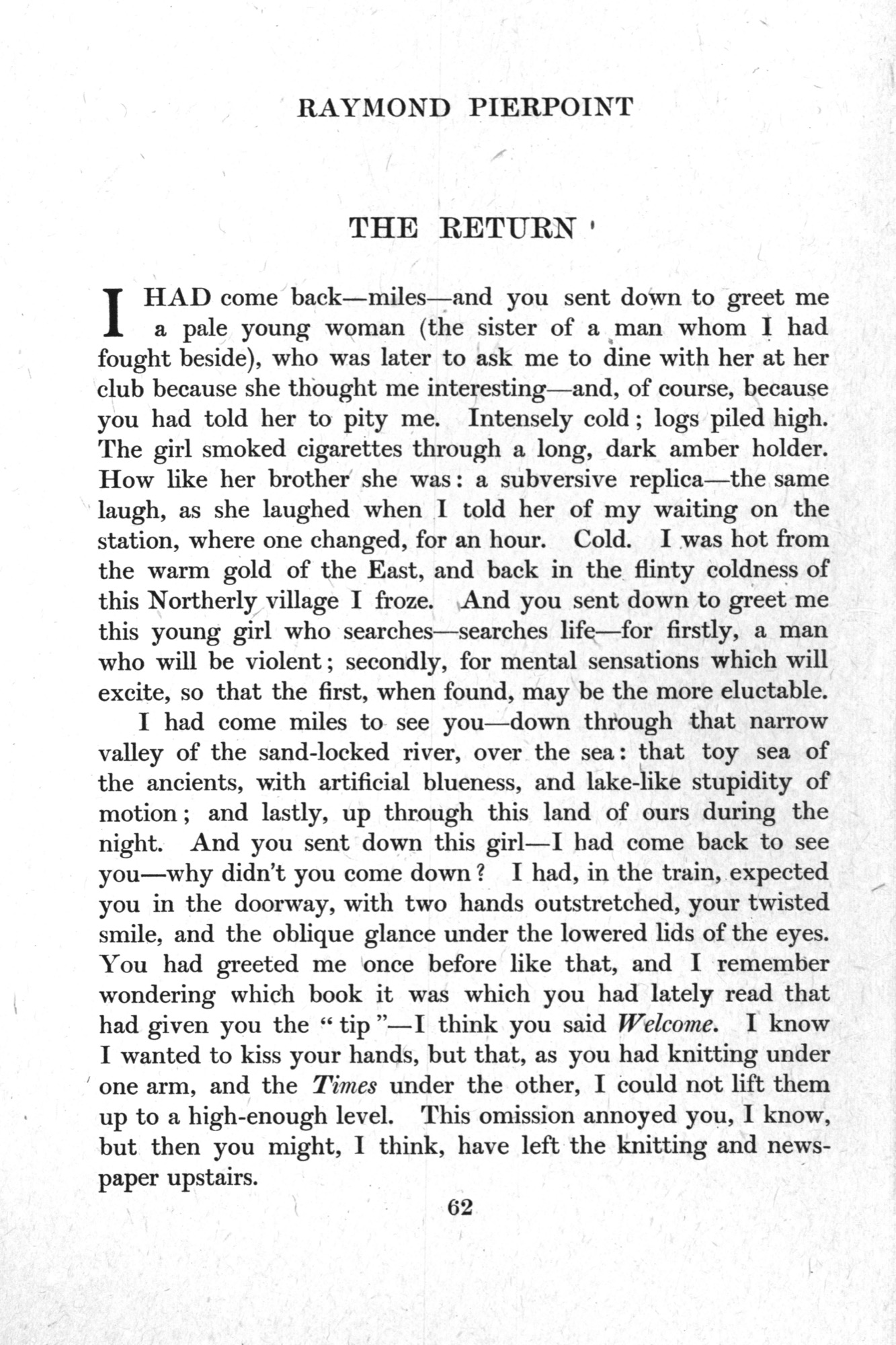

| Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 5 Autumn 1920 Page: 62 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Return | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

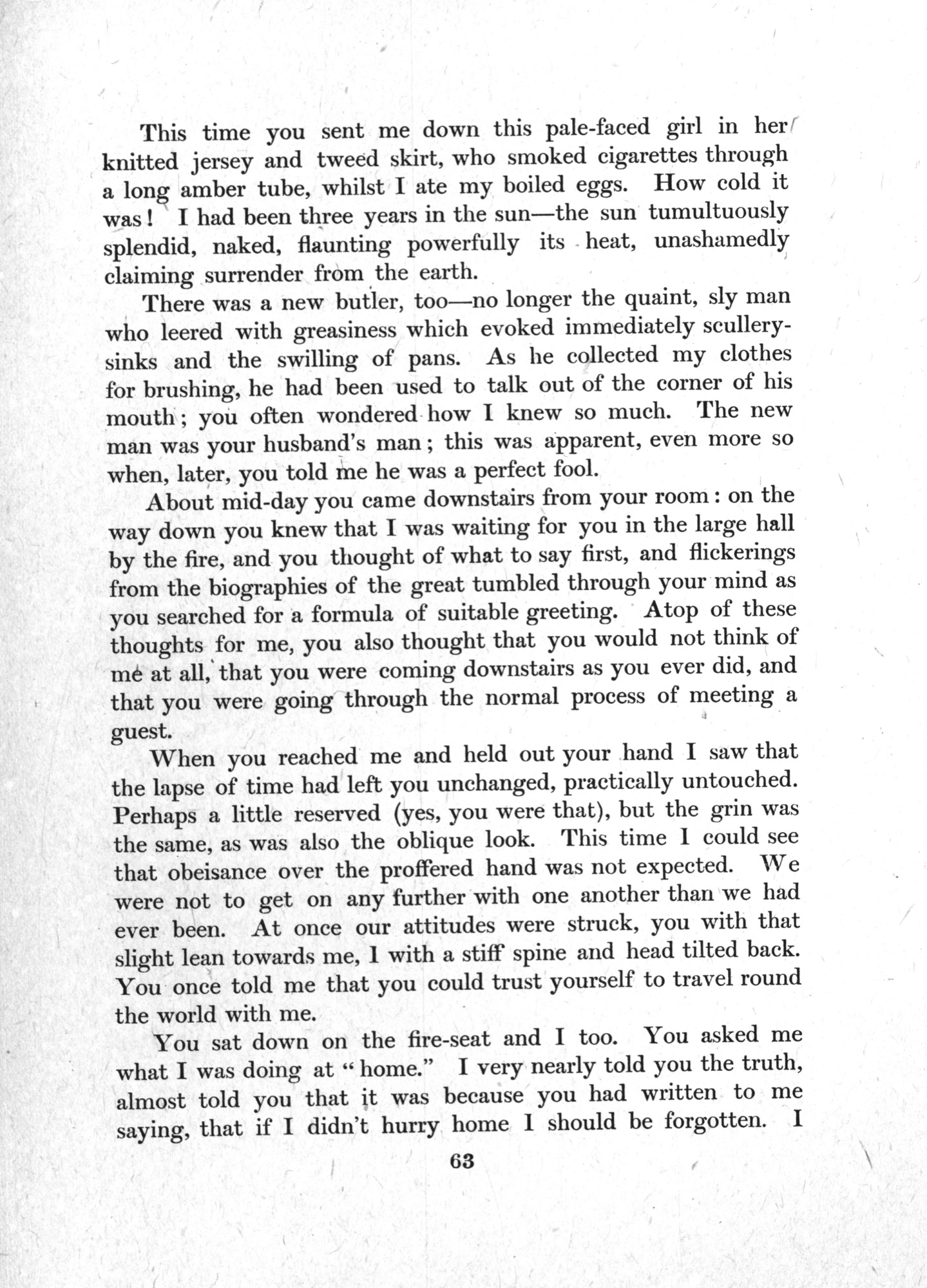

| Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 5 Autumn 1920 Page: 63 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Return | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

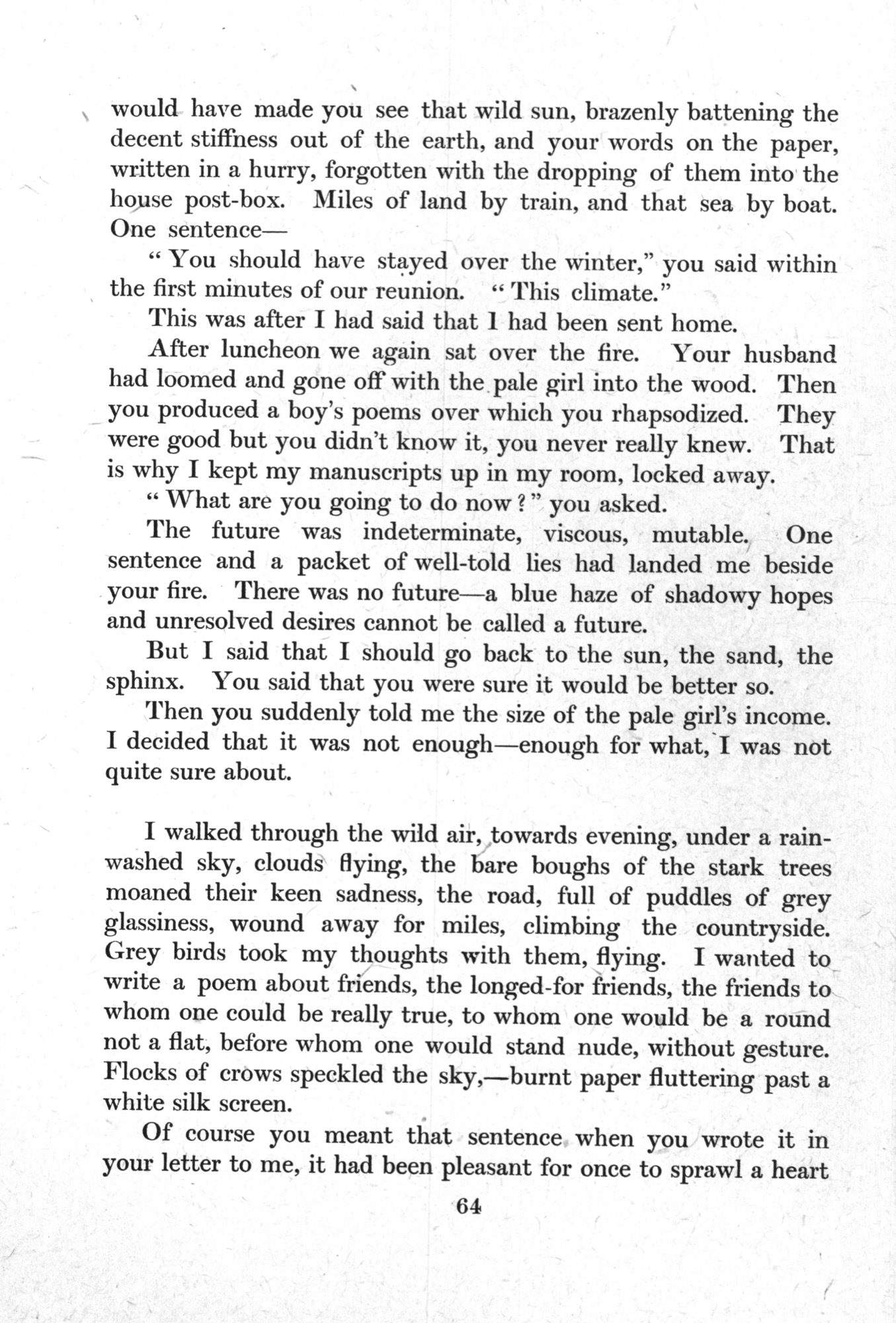

| Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 5 Autumn 1920 Page: 64 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Return | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

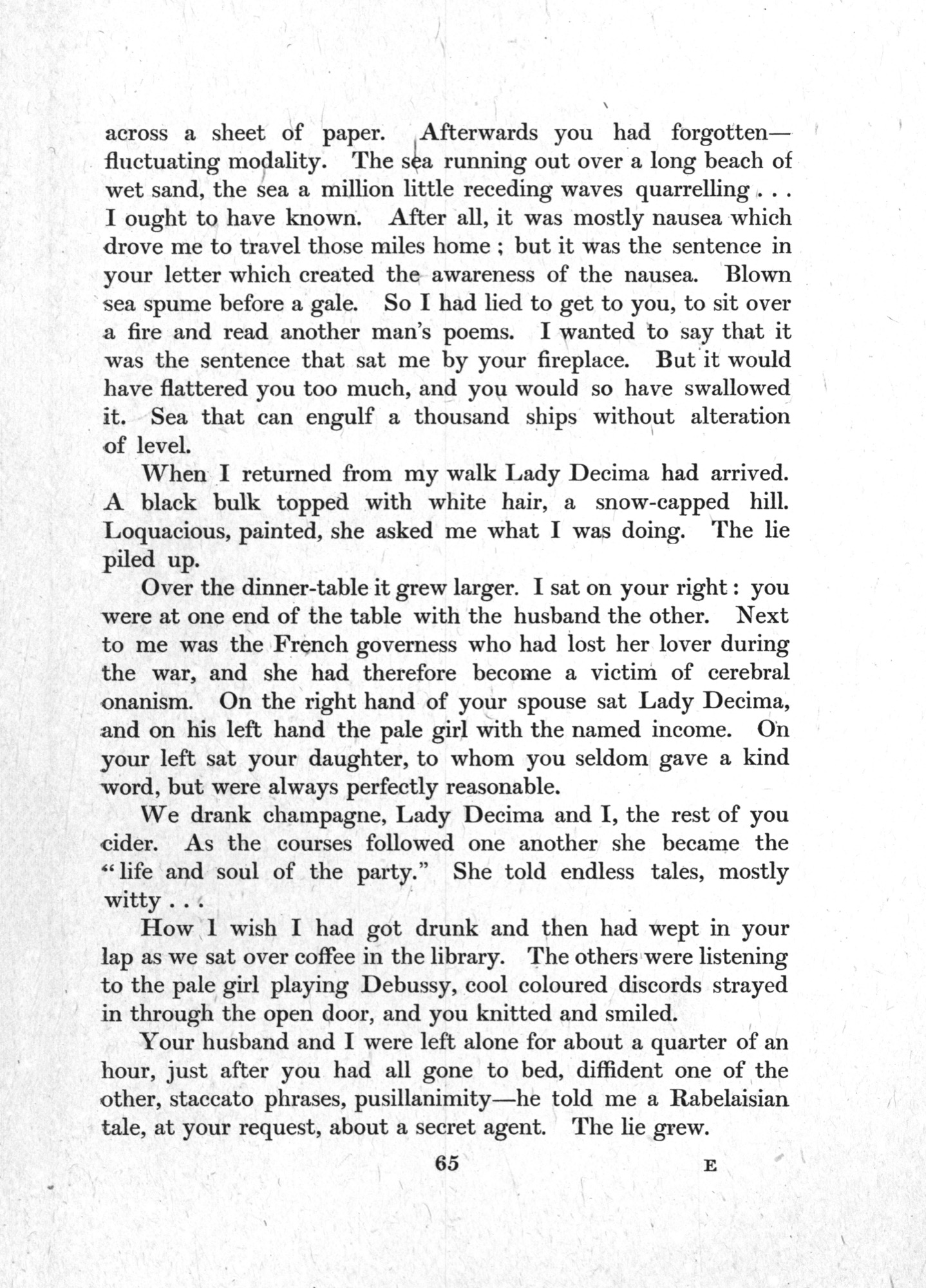

| Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 5 Autumn 1920 Page: 65 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Return | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coterie Volume 1 Issue: 5 Autumn 1920 Page: 66 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Return | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||