1 of

You are browsing the full text of the article: Some Letters of Richard Middleton

Click here to go back to the list of articles for

Issue:

Volume: 1 of The Gypsy

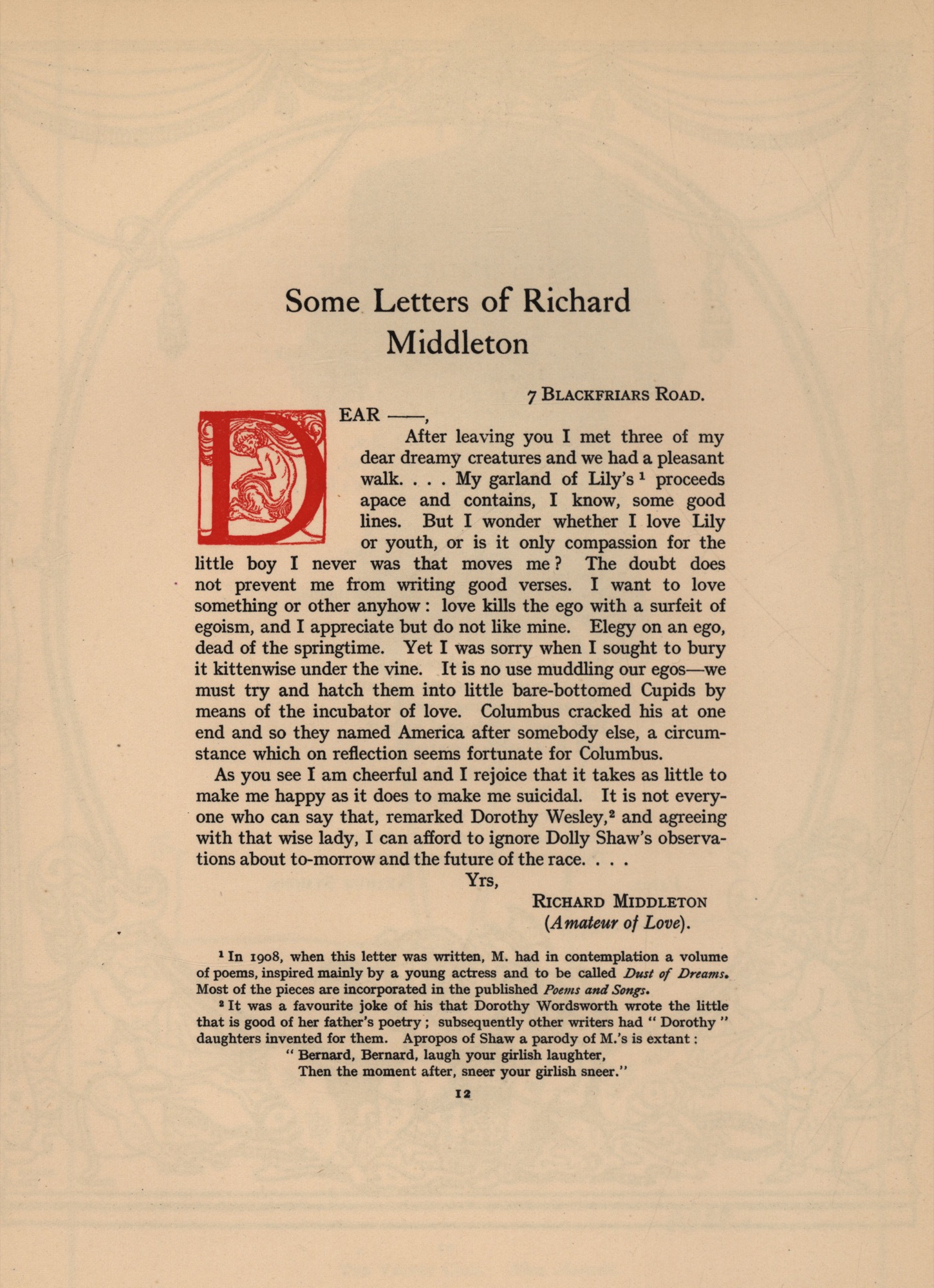

| The Gypsy 1 Issue:: 1 1935 Page: 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some Letters of Richard Middleton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

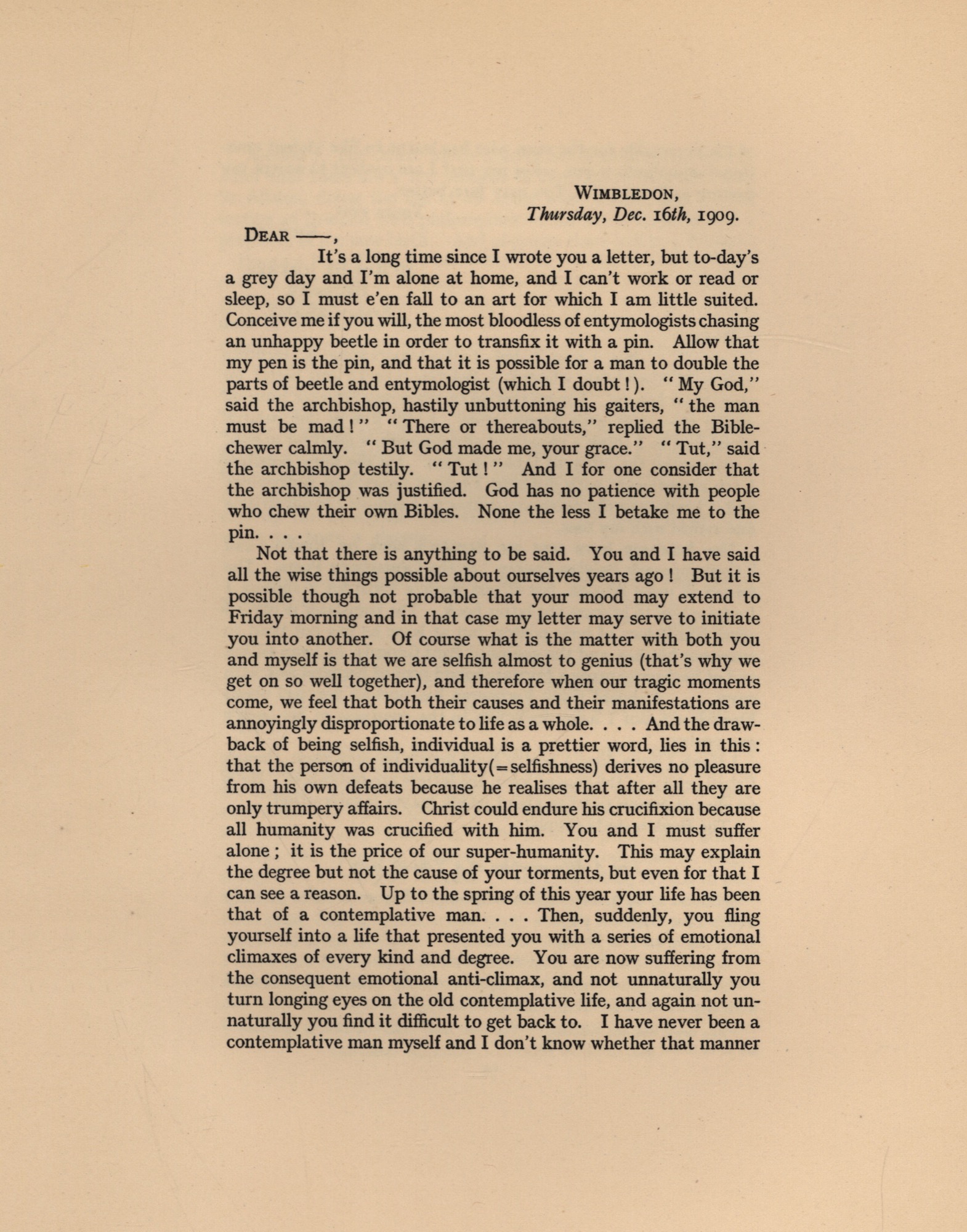

| The Gypsy 1 Issue:: 1 1935 Page: 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some Letters of Richard Middleton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

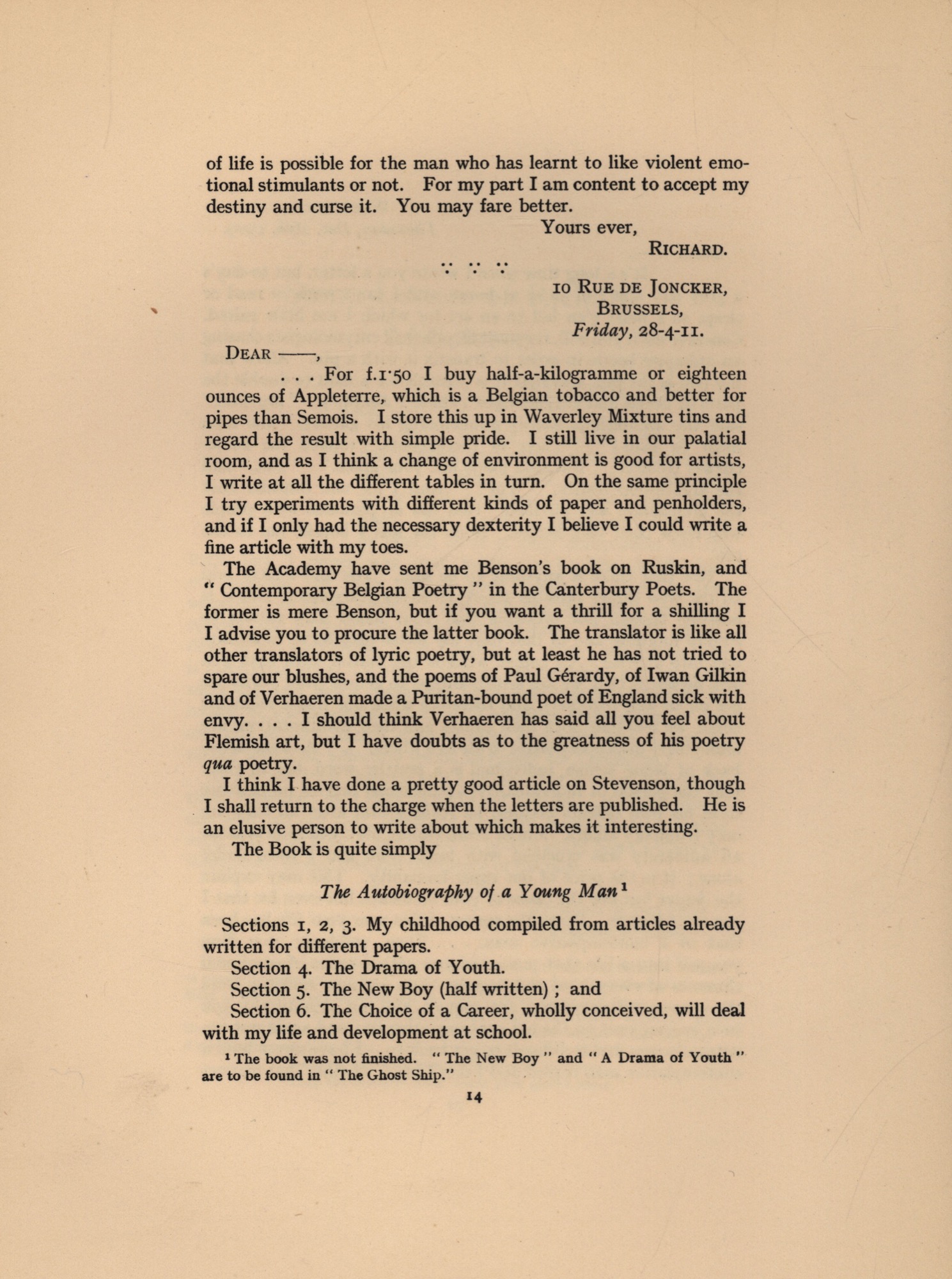

| The Gypsy 1 Issue:: 1 1935 Page: 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some Letters of Richard Middleton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

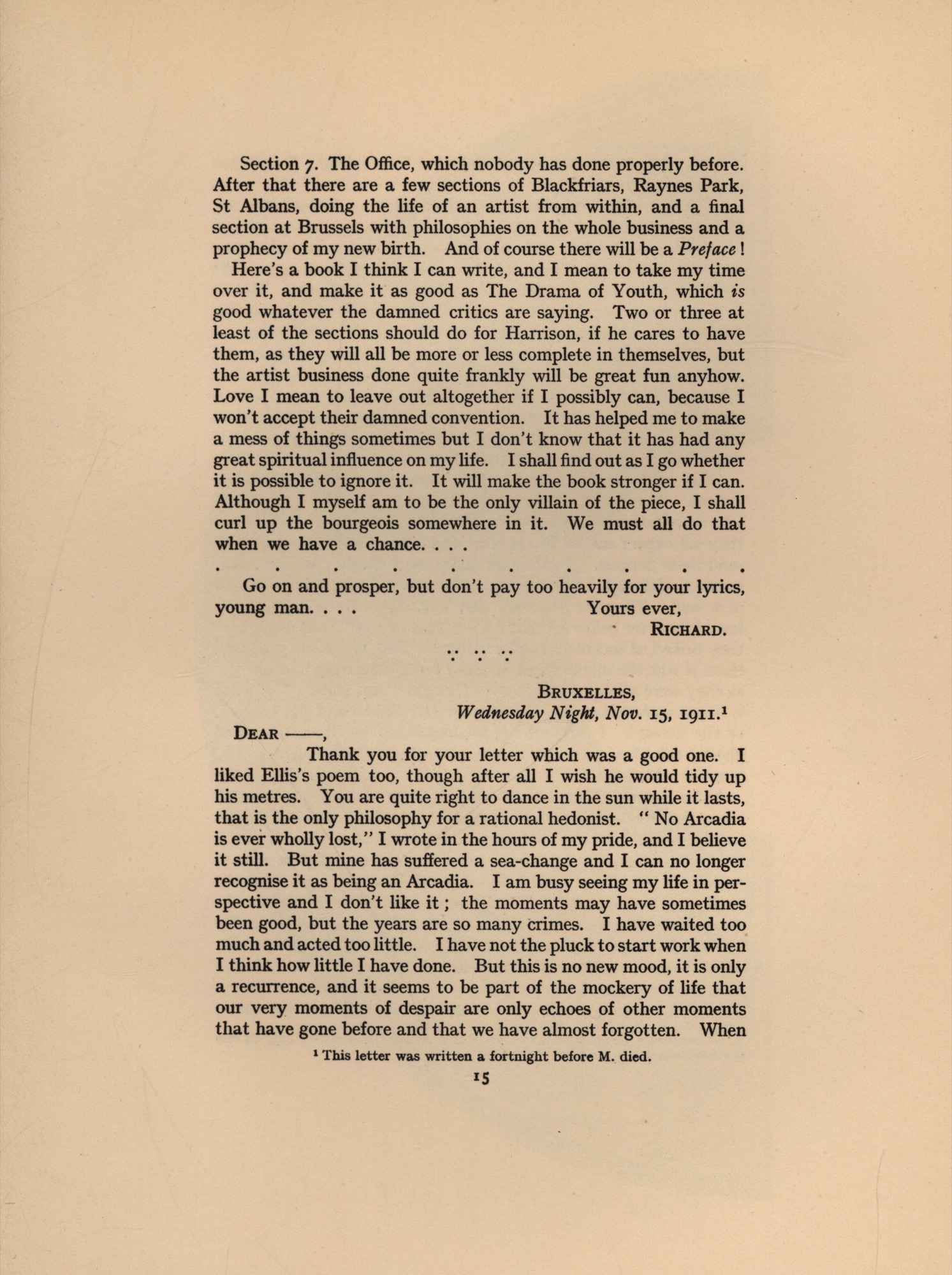

| The Gypsy 1 Issue:: 1 1935 Page: 15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some Letters of Richard Middleton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

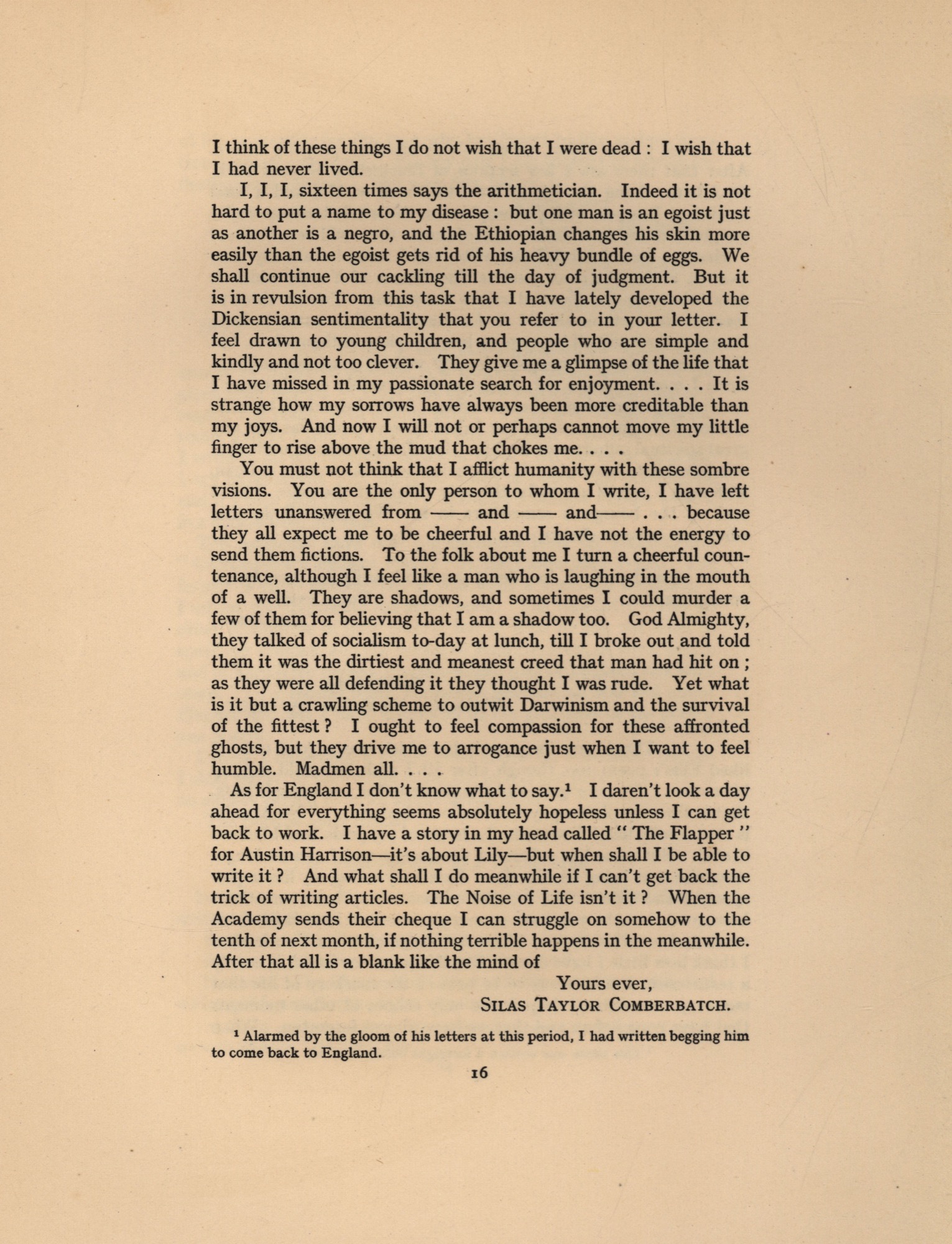

| The Gypsy 1 Issue:: 1 1935 Page: 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Some Letters of Richard Middleton | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||