1 of

You are browsing the full text of the article: Private Collections of Ancient Sculpture in Rome

Click here to go back to the list of articles for

Issue:

Volume: 2 of The American Art Review

| The American Art Review Volume 2 Issue: 1 November 1880 Page: 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Private Collections of Ancient Sculpture in Rome By Thomas Davidson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The American Art Review Volume 2 Issue: 1 November 1880 Page: 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Private Collections of Ancient Sculpture in Rome By Thomas Davidson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The American Art Review Volume 2 Issue: 1 November 1880 Page: 9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Private Collections of Ancient Sculpture in Rome By Thomas Davidson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The American Art Review Volume 2 Issue: 1 November 1880 Page: 10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Private Collections of Ancient Sculpture in Rome By Thomas Davidson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The American Art Review Volume 2 Issue: 1 November 1880 Page: 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Private Collections of Ancient Sculpture in Rome By Thomas Davidson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

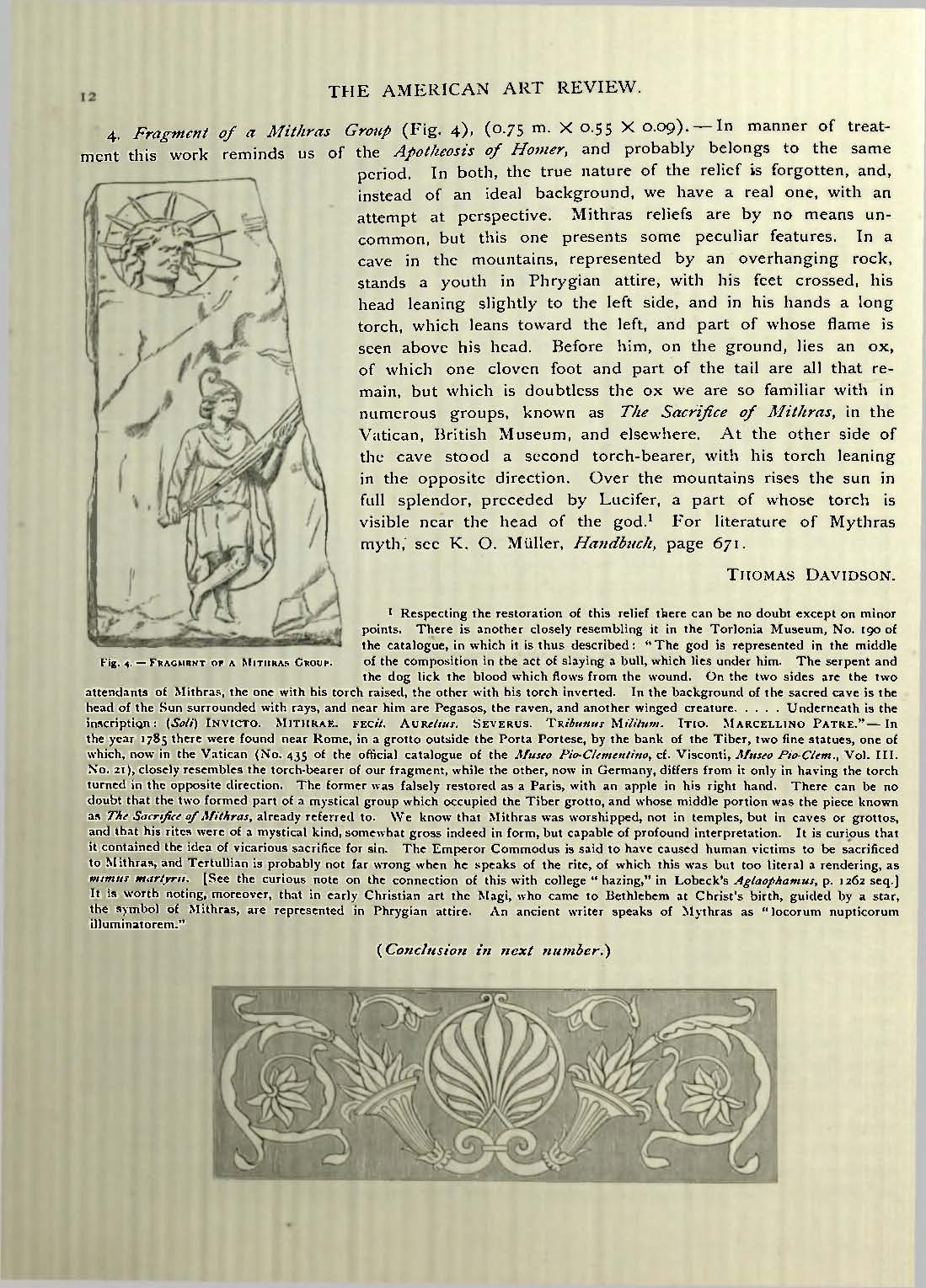

| The American Art Review Volume 2 Issue: 1 November 1880 Page: 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Private Collections of Ancient Sculpture in Rome By Thomas Davidson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||